Too far did I fly into the future: a horror seized upon me.

Nietzsche in Thus Spoke Zarathustra.We call our fathers fools, so wise we grow,

Our wiser sons will no doubt call us so.

Alexander Pope in An essay on Criticism.Once upon a time, Mother Earth was in trouble. She asked Ahura Mazda (God) if he would send her a prince, with warriors, to stop the people from hurting her, using force. But Ahura Mazda said he could not. Instead he would send Her a holy man, to stop the people from hurting her, using words and inspirational ideas. And thus was born the prophet, Zarathustra.

Zoroastrian legend

––––––––––

PART 1

What better than returning to the roots of civilization to raise awareness about the dangers facing humanity today? This is particularly the case when the cultural group in question – the Zoroastrians –are thought to have disappeared long ago by most people, included the educated ones. However, the followers of Zarathustra are not mere fire worshipers of the past. They are the believers in an avant-gardist religion, born more than 3000 years ago, that promulgated care for the elements and the Earth and the protection of the environment as their first, if not their primary principles. More importantly: they still represent a vibrant– though threatened – community, and need being heard, at a time when climate change has become the final outcry of a deeper, multifaceted global environmental crisis.

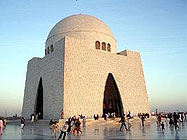

I met them in Karachi, a megacity in the south of Pakistan, which in many ways concentrates all the ailments of the above-mentioned crisis: pollution, water scarcity, lack of urban planning, demographic crisis and disrespect for all living things.

My first encounter was with Ardeshi Cowasjee who is 82 years old, and one of the most prominent journalists in his country. He humbly welcomed me at his home. He was delighted to show me his magnificent garden, adorned with a 150 year old banyan. His three dogs came to greet me in all confidence. Ardeshi would under no circumstances leave Karachi, the town where he was born. It has tremendously changed for the past thirty years, but he still loves it as much as ever. Soona Dhatigra, an 88-year-old woman interviewed by Parsikhabar online magazine, somehow sounded more nostalgic. She said that Karachi used to be a clean and good city to live in: “There was no overflowing sewage or noise pollution”. She still remembered the glorious times of Jamshed Nusserwanjee Mehta, one of Karachi’s most distinguished and beloved icons. Mehta had the unique distinction of being elected the Mayor of Karachi for twelve consecutive years in the 1930s and is fondly remembered as the “Maker of Modern Karachi”. He was one of the rare Zoroastrians ever to hold this position. Meher, another Zoroastrian who I personally met at her home, remembered from her childhood that the streets of Karachi used to be washed every night. Now it has deteriorated. Trees are cut down. Parks are taken over by rubbish. When it rains, life comes to a standstill. There used to be trams but now mafias control the entire traffic network.

The good old system ended with the partition of the subcontinent in August 1947 and the creation of Pakistan, when the population of Karachi stood at some 450,000. “An almost immediate influx of some 600,000 refugees from across the border brought up the population to just over a million and thus began the degeneration, with a steady flow into the city of the horde. For a city to more than double its population almost overnight did not bode for happy, orderly or progressive times”, as Ardeshi narrates.

The Zoroastrian community of Karachi, known as Parsis (since their ascendants came from ancient Persia), has since then drastically dwindled. Toxy, a Parsi social worker and editor for the World Zoroastrian Organization, holds a register to keep track of population figures. By April 2009, she recorded 1822 Parsis in Pakistan, of which 1741 live in Karachi. Since then many have passed away. Other people estimate that the actual population has already fallen down to 1200. This trend also reflects what is happening in neighbouring India, where according to the 2001 Indian census, the Parsis numbered 69,601, representing about 0.006% of the total population. Due to a low birth rate and high rate of emigration, demographic trends project that by 2020 the Parsis will number only about 23,000 or 0.002% of the total population of India. They would then cease to be called a community, and be labelled a „tribe“. By 2008, the birth-to-death ratio was 1:5, i.e. 200 births per year to 1,000 deaths according to the information collected by Andrew Buncombe, a journalist at The Independant. According to Toxy, such projections are too optimistic. She insists that many voices in the community are warning of the day, not far off, when the community will disappear. However, faithful adherents express their confidence that this will never be so. Others are awaiting the appearance of the messiah Bahram Varjavand to see the community thrive again.

The Parsis have been some of the best witnesses to the environmental failure that characterized Karachi, and maybe its first victims. In Saadar bazaar, Zarin, a 65 years-old Parsi whose only son has migrated to the United States, shows me a great number of buildings that used to belong to her community. These are now abandoned and in a condition of decay. The Parsi colonies, once located at the edge of town, are now surrounded by slums. In one of these stands the Tower of Silence, or Dokhma, where funeral ceremonies take place. It is a symbol par excellence of the special relationship that Zoroastrians try to maintain with Mother Earth. Their ancient ancestors realised that a dead body begins to putrefy within hours of a person’s death and becomes a source of contamination. It should, therefore, be disposed of as quickly as possible so as not to pollute any of the four elements. The Tower is thus located on heights where the powerful rays of the sun clean the remains and the vultures finish the job within hours. Zoroastrians use no chemicals, no herbs and no powders, and it is a standard practice for the bones to be piled after a year in the central well where they crumble to ash. At the end of 1990 the well of the main Dokhma in Karachi was cleaned after nearly 100 years. Zoroastrians find it the cheapest, the simplest and most egalitarian method, as well as being hygienic and ecologically sound.

Considering the unique role Parsis have played over the years in the building of Karachi, the current crisis is greatly unfortunate. Community members like to retell the story of their arrival in India some centuries ago when their priests promised the Hindu kings they would be like sugar added to a bowl of milk, meaning they would mingle into the local population and try to be as helpful as possible, and to date, this has proved true. Mahatma Gandhi himself said that Parsis were “in number beneath contempt, but in charity and philanthropy perhaps unequalled, certainly unsurpassed”. Throughout the Indian subcontinent the Parsis have always enjoyed tolerance and even admiration from other religious communities. A peace loving people, they now keep well away from politics but this has not always been the case. From the 19th century onward they gained a reputation for their education and widespread influence in all aspects of society, partly due to the divisive strategy of British colonialism which favoured certain minorities. Parsis are generally more affluent than other Pakistanis and are stereotypically viewed as among the most Anglicised and „Westernised“ of the various minority groups. They have also played an instrumental role in the economic development of the region over many decades; several of the best-known business conglomerates of India are run by Parsi-Zoroastrians, including the Tata, Godrej, and Wadia families.

Parsis reject dependency on others and theft of property: instead, each and everyone has to make a living from their own efforts in order to benefit from their own harvest. Also, they insist that disparity between the rich and the poor has to be resolved. The creator provided enough for each and every creation. It is the greed of human beings that leads to the unequal distribution of income and wealth among people. Asked by Dr Lata Narayanan from Tata Institute for Social Science to state the five values they strongly believed in, 69% of the interviewees – all young Parsis from Mumbay – spoke of honesty and integrity, 34% of respect for elders, 31% for truth, 27% for importance of action and hard work, 25% for loyalty.

But now that the civilisation is in a shambles, the Parsis know they have to do more for the helpless who have no voice and who are sadly completely at the mercy of the wealthier. How can they set this plan in order when they now represent an invisible minority in a megacity like Karachi? Numerous Parsi foundations exist to cater for the needs of the poorest members of their own community, but they do not have the capacity to respond to the tremendous needs throughout the rest of society.

However is Zoroastrianism not regarded as a unique ecological religion? If this were so, the Parsis would endorse our global responsibilities and be at the forefront of environmental consciousness-raising: by tradition, they all carry social responsibility towards the future of the planet’s wellbeing as Zarathustra taught his followers to be constantly active in furthering creation. And humankind, as the seventh creation, should protect the other six (sky, water, earth, plant, animal, and fire). However, their biggest challenges lie ahead, and they still have to find ways to hopefully make a meaningful contribution to improving the prospects of humanity.

“Thou shalt not pollute Mother Earth” is the first injunction of the Zoroastrian religion. “Nor shalt thou pollute the life-giving waters, nor defile the sacred fire, nor pollute the air”. According to Zarathustra, this sacredness of the creations demands a greater awareness, for at the end of time humanity must give to Ahura Mazda (God) a world of purity, a world in its original perfect state.

PART 2

An example of the Zoroastrian’s concern for the environment is their tradition to never enter a river, to wash in it or pollute it in any way – purity of nature is seen as the greatest good. And as care for both the material and spiritual aspects of their existence is a religious duty, their life needs to exhibit simplicity, selflessness, charity and of course purity. Purity of the body leads to purity of the mind. Thus spoke Zarathustra at the dawn of civilization some 3000 years ago:

“Aevo Pantao, yo Ashae” (One alone is the path and that is the path of purity)

“Mashiao Aipi Zanthen Vahishta” (Purity is the best way for man from his birth onwards)

But while Zoroastrian purity laws are comprehensive, they are now largely neglected by contemporary urban dwellers: what respect is shown to Mother Earth in an environment such as Karachi? As rightly put by the Zoroastrian writer Shahin Bakhradnia, the mantra of good thoughts, good words and good deeds is the way to be truly fulfilled Zoroastrians and is also the means to get there. This is how to make the conscious choice of the path of Asha – purity/righteousness – which leads towards such a saintly state of being.

Shahin added: “I say saintly advisedly, because quite frankly anyone claiming to have already achieved this state of purity in thought and word and deed must indeed be out of the ordinary and already in a state of sanctitude or merely be extremely arrogant”. Since my arrival in Karachi, I have met a number of Parsis who humbly confirmed that indeed, this is not an easy claim. Ben Harfer, a Parsi who married a Muslim man, told me that even though she renounced to her faith, she is still striving to follow good words, good thoughts, good deeds. Thrity, another Parsi from Karachi, said that she sometimes goes and prays not in the temple but near noble trees, or by the sea on Hava Roj, the monthly day of water, since all elements are created by Ahura Mazda. Her niece’s daughter is also called Hava – water in Persian.

I also went to Sandspit, the only preserved coastline in the region of Karachi, a place of wilderness, where Aban Marker Kabraji, now head of IUCN for Asia, has initiated a project for the conservation of endangered Green Turtle population. At her side, her sister Meher explained to me how Parsis plant a tree to celebrate the birth of a new family member and for weddings they used to plant a mango tree, but now they content themselves with a symbolic branch. Parsis are brought up with the need to have a garden for greenery, flower, trees, fruits, and all gardens have coconuts which are used in rituals. Traditionally, even before planting a seedling in the earth, man held the plant in both hands and slowly turned to the four directions, offering the plant to sun and shadow, wind and rain, moonlight and the birds and animals. The words recited were „Nemo Ve Urvaro, Mazdadathe Ashone“, „Homage to you O‘ Good and sacred plant created by Mazda“ and were followed by the Ashem Vohu prayer. Mrs Parakh, headmaster of a Parsi school in Karachi, is proud of the vital teacher-pupil rapport in her school: ‚We inculcate in our students the importance of ‘going green’. It’s not just the historicity of the institution that the children are conscious of, they’re cognizant of the environment as well. Since they’re aware, they can’t vandalise.‘

With this philosophy in mind, people should neither speak badly, nor behave badly in society. Aban Marker Kabraji, interviewed in 2006 by Sahar Ali of the Pakistani online newspaper Newsline, stressed how important it is to “work on the premise that people are basically of good will and want to make things better. Because if you start with a suspicion that people are mala fide-intentioned, you will get nowhere. Start with the assumption that you can trust people, and people rise to that expectation”. However, within the Pakistani society, Parsis often face conflicting situations. How can one react to cultural clashes when the basis for one’s religion is tolerance? Among Parsis, for instance, animals are treated well, especially dogs, which severely contrasts with the rest of society. Zoroastrians maintain that no harm should be perpetrated against animals and condemn the cult of haoma, that includes the sacrifice of the bull, the most sacred animal and in general, Humans have been given the responsibility to fight anything that is detrimental to the purpose of creation, because all are interconnected to each other. Some situations may, therefore, become unbearable.

Many Parsis reject, for instance, the unnecessary suffering resulting from some festivals, when animals are brutally slaughtered in the streets of Karachi. Ardeshi Cowasjee wonders: “We have two meatless days a week in this country which can only denote a lack of livestock: does it make sense that over the span of three days each year, in one city alone over a million prime breeding stock is slaughtered […] as an exhibition of wealth coupled with vulgarity? […] Not only does the blood and gore further choke our already choked gutters, but the muck is carried into the sea surrounding Karachi which is already calculated to be around 90 percent pure sewage”.

In terms of environmental damage, tolerance also has its limits. The truth is, as in other developing countries, Pakistan suffers very much from a lack of education. Commoners have heard about climate change but do not know its causes. For them the main aim remains survival. However, what many of us know is that climate change will intensify weather patterns and these will become more and more dramatic. What cities and countries have to be prepared for is years of drought, or years of floods. You cannot count on what is going to happen anymore, as the whole atmosphere is now in a state of instability. What Karachi should brace itself for is massive floods. There could even be tsunamis which the population is totally unprepared for. For Aban Marker Kabraji, “this is ridiculous because I live in a city like Bangkok which gets monsoonal rains continuously, but has a phenomenally good drainage system. So the problem is not that the knowledge is not there. Our infrastructure is abysmal. And it’s abysmal because of bad governance. Our infrastructure is of poor quality, and there is obviously no accountability”.

Karachi has already grown far too large and is drowning in its own effluent and pollution. Law and order problems increase proportionately to the population, and with the increasing discrepancy between the haves and the have-nots. The Quran however states that human habitations must not be made too large, and a new, separate habitation must be established when one has expanded to the extent that people no longer recognise one another. Meanwhile, in a special report on world megacities, published by IEEE Spectrum – one of the world’s largest professional technology association -,, Karachi was named twice. First, as it had by far the worst pm10 problem in 1999 – the last year for which complete data was available. The situation has surely grown far more serious since then. Particulate matter smaller than 10 micrometers in diameter (pm10) is the most dangerous to human health, because it can pass through the nose and throat and enter the lungs — leading to asthma, lung cancer, cardiovascular problems, and premature death. In the same report, one graph which showed the slum populations. It ranked Pakistan as having the fifth largest slum population, way behind China and India in numbers. However, 74% of urban dwellers in Pakistan live in slums as opposed to 56% in India and 38% in China. In the National Geographic magazine, an author said that in Asia, Karachi’s Orangi Township had surpassed Dharvi, in Mumbay, as being the largest slum in Asia…

Ardeshi Cowasjee, who gathered these figures, has been a constant advocate for better environmental policies in his municipality. He proclaims that “we are all acutely aware that when the government of [the province of] Sindh and its administration (or for that matter any government and administration of Pakistan) wishes to actually do something – naturally not for the good of the people but to achieve their own ends via their own means – they can do it, and do it rather effectively”.

Nevertheless, Karachi’s transport system, a matter of great havoc in the city, has been in a mess since the late 1970s. The present problems at hand are so critical that the ‘do-nothing option’ which has prevailed, is no longer an option. Ardeshi Cowasjee suggests that unless the government takes concrete steps to enforce traffic discipline, to implement the driving rules, and to remove road friction (such as illegal parking, loading and unloading of vehicles, encroachments), Karachi is opting for disaster in the near future. While the population explosion pressure and the escalating transport problems all point to a mass transport system as the solution, those who run this city go for the construction of mega-projects such as underpasses, overpasses and elevated expressways despite experts, including architects, engineers, planners and advocacy groups rejecting these projects on environmental grounds.

Ardeshi Cowasjee also explains how in mid-2006, a Dubai-based developer, Limitless of Dubai World, sold a hare-brained scheme, Sugarland City, to the prime minister Shaukat Aziz, whose stated intent was to convert Karachi into a ‘world-class city’. The project envisaged the transformation of some 65,000-plus acres of land into “the most exciting 21st century urban quarter in the world”. Concerned citizens and civil society groups in the city reacted strongly to this takeover of the coastline and the promotion of a grandiose project totally unrelated to the realities of life in Karachi. Adverse news items, letters to the editor, seminars and public statements by politicians, demonstrations by affected fishermen, and court cases by beach-hut owners began to multiply the following year. A coalition of these protestors was formed, called Dharti (sacred land), whose aim was “to synergise the diverse capacities of civil society organisations convinced about the centrality of the environmental framework within which all human activity takes place, in order to ensure that all actions undertaken by official and non-official sectors in Sindh, in particular, and in Pakistan, in general, respect the abiding values of ecological sanctity and of human well-being”.

Aban Marker Kabraji sounds more optimistic. For her, with economic indicators rising, and in spite of the global financial crisis, the bullish economy will bring expatriate Pakistanis back to the country, which in turn will bring about an openness and tolerance in Pakistani society. „It may not happen for another 20 years. We can only be part of this process of change, and make sure we accelerate it as much as possible,“ she says. She also explains that much of her struggle has been “to make policy-makers realise how closely linked the environment is to poverty. That the poor base their livelihood almost entirely on natural resources, so the decline of our forests, rivers, rangelands, soils, seas, and the wildlife that inhabit them, plunges people deeper into poverty”. The impact of pollution is greatest on the poor. The poorer you are, the worse you are hit by any kind of degradation. Aban Marker Kabraji continues: “For example, they are unable to access safe drinking water, so they drink from lakes and streams in rural areas, or any kind of tap that is available. In cities, they are usually in those parts where pollution is the worst, so the impact of a degraded environment, urban or rural, is greatest on the poorest.

She, however, recognizes that if judged in the same way as social indicators like health or education, environmental success faces similar political, economic and social constraints that keep Pakistan in the lower category of developing nations, thereby further undermining environmental achievements.

For Aban Marker Kabraji, the principle of economic growth is however not something one could argue with: “You have to be able to resource environmental management, and the best way is through a thriving economy. The model of economic growth and its associated consumerism, which is unsustainable, is of course a dilemma. But you certainly need the economic prosperity to be able to fund environmental plans. The question is getting the balance right. Right now, we haven’t got that balance, nor have we got the investment in the right places. I’m sure this is not a very popular opinion because in the west all the environmentalists are beating their breasts that consumerism has gone wild, which I agree. But between that unsustainable model and a kind of utopia, where you live entirely in a world of sack cloth and ashes, there is a middle path. No country has found it, but you have to strive to get there”.

Some 3,000 years after Zarathustra, the Western world has produced people known by the fancy names of ecologists, conservationists, environmentalists and restorationists. They teach the selfsame lesson, “keep the four elements pure and clean”. The slightest misuse, disuse, or abuse of these elements, they say, will cause untold damage or even irreparable disaster to the planet. Does this text resonate with their way of thinking about the contemporary crisis? It has to be clear that this article is not merely about the religion of Zarathustra. Across its lines, every human being can be considered as a Parsi and every place on Earth a duplicate of Karachi. For both humanity and civilization may dwindle and then collapse if nothing is done to reverse the catastrophic path currently taken.

Last question: will the leaders who have assembled at Copenhagen listen to this voice of prophecy, and if so, what will they do about it?

© David Knaute, 17.12.2009

Fotos: David Knaute

–––––––––––––––

Biography

David Knaute is a French-Czech citizen who has been working for the past 6 years in the humanitarian sector in Asia and Africa. He has participated to the production of two documentary films and edited one book on minority groups. He is currently working and living in Karachi, Pakistan.

–––––––––––

References

(all websites have been last accessed on 29/11/2009)

Book

F.K. Dadachanji, 1995, Speeches and writings on Zoroastrian Religion, Culture and Civilization, Ehtesham Process. Karachi, Pakistan.

Online press article

- Karachi 2007, Ardeshi Cowasjee, the Dawn , 07/01/2007, online

- numero uno, Ardeshi Cowasjee, the Dawn , 10/06/2007, online

- Whither Karachi, Ardeshi Cowasjee, the Dawn , 17/06/2007, online

- Threat to Karachi’s seashore, Ardeshi Cowasjee, the Dawn , 16/03/2008, online

- The state of our civilisation, Ardeshi Cowasjee, the Dawn , 21/12/2008, online

- Interview with Aban Marker Kabraji by Sahar Ali, Newsline, October 2006, online

- Good deed, great building, Peerzada Salman, the Dawn, 06/09/2009, online

Online press article

- Wipedia: Zoroastrianism

- Vohuman.org

- No vultures since 1956: letter from the Karachi Parsi Anjuman, Byram D. Avari, online

- Environmental concerns: Zoroastrian responses, online

- Parsiana April 7, 2009, A journey of Discovery: II, Arnavaz S. Mama, online

- Zoroastrism and humanity, best days yet to come? HAMZOR, issue 3, 2003, pps. 30-31, online

- The Unesco Parsi Zoroastrian Project: religion and priesthood, online