Opening day and first day (17th-18th)

The Ueber Lebenkunst festival is is the climax of the Ueber Lebenkunst initiative (ULK), a 3.5 million euros, 1 year long project initiated by the German Federal Cultural Foundation in cooperation with the Haus der Kulturen der Welt (HKW). ULK aims to “examine perspectives of economic and social restructuring that could lead to a sustainable way of life and investigates what kind of role culture can play in such a process”.

The festival includes a wide range of activities, including a conference with world-renowned speakers, a number of performances, workshops, excursions, installations, food-related events and more. The festival is also the occasion for the presentation of several school projects carried out in the past year as part of the “Ueber Lebenkunst Schule”. I will not be able to mention them all here (see the festival details at http://www.ueber-lebenskunst.org).

On the evening of August 17th, the conference opening starts in a sort of firework-style, with activities all around the HKW premises. The large auditorium of the HKW is fully seated (unlike in the following days, where the audience in the auditorium will be on average reduced to between 60 and 120 people). Some of the key features of the festival are highlighted: One is the fact that the conference, in the auditorium, is connected, via live satellite stream, to Nairobi, Delhi, St Petersburg and Sao Paulo, from where some conference sessions and performances are to take place.

The live streams format aims of course to minimize the festival’s ecofootprint. The festival (and the ULK initiative in general) also aims to directly affect “the house” of the HKW, in order to introduce sustainable practices into the daily activities of the house. The whole process is being monitored.

Following the official opening in the auditorium, several of the initiatives and installations in the HKW are presented throughout the evening/night. The atmosphere is lively, fussy and messy, with installations, activities, workshops and performances scattered across the HKW building and on its terrace. Numbers-wise, the opening evening is a big success, with an audience of several thousands crowding the place. However, like at many openings, this first contact leaves only superficial, blurry impressions, besides the occasion for socializing.

On Thursday, August 18th, the festival really begins. At midday, I follow the first session of the conference, which features two speakers: the sociologist Arjun Appadurai and the artist Kris Verdonck. The first session’s topic is dealing with art & technology. In his short introductory statement, HKW Director Bernd Scherer warns about technologies as fragmented systems (“Teilsysteme”) that shape problems and then (cl)aim to solve these problems within themselves.

Appadurai’s speech deals with innovation & imagination, and the semantic gap that has unfortunately arisen between the 2. Both relate to the space of the new, but innovation relates to technologies and markets, while imagination relates to art. Appadurai asks: Can innovation thrive without destroying older styles? He quickly discusses the “design of everyday life” in Indian slums (e.g. in local efforts to build community toilets there), the ownership of design by local communities, and how “the local is always produced” (rather than merely given). Appadurai argues that all communities are to some extent designers and planners, and that an enormous range of design solutions emerged especially from pre-State societies. But he warns against the prejudice that design can create indefinite, unlimited combinations in fashion, and rather sees design as slowing down and disciplining imagination. Appadurai talks of “ inanimate things that make demands” (which could points at Bruno Latour’s actor-network theory, but Appadurai doesn’t mention that). Fashion, on the other hand unsettles contexts, stirs the pot, fosters disturbance, while planning, unlike design, is fundamentally a State activity. Appadurai then spends some time criticizing markets and rational choice theory, and asks how planning, sustainability (which he defines rather disappointingly as being about the long term) and design can work together. His conclusion is that “ innovation without imagination has no ethics. Imagination without innovation has no lasting social effects.”

Overall, Appadurai’s lecture offers a few interesting points, but only remaining at a superficial level, does not dig deeper into any single of them.

Kris Verdonck’s speech focuses on infantilization through technologies, and on our extreme dependency on them. He uses several clear images, such as the one of the car driver at 200 km, with everything being made soft in the car, adapting to the increasing speed. Verdonck points at a technological environment as “we would love to have it”, with machines as our best friends. We do cry when R2D2 dies in Star Wars… Besides, you can make machines die for real on stage, unlike the human actors who only act as if they were dying. This brought Verdonck to create performances for machines, or performances with machines and humans where the former are the main actors and the latter are mere passive props.

With its bitter-playful irony, Verdonck’s intervention hits right to the point, critical of so-called green innovations, green revolution, new clean cars, and highlighting our intense emotional attachments to an advanced technological system that has deeply modified our experiences of reality. I was relieved, thanks to Verdonck’s intervention, that this conference session did not end up in the techno-naive, ecological modernization discourses that are still dominant nowadays, in the mass media as well as in the ‚art world‘ of contemporary art.

I am not staying very long at the second session of the conference, with Jennifer Morgan, Nnimmo Bassey and Daniel Klingenfeld. They are discussing international climate policy (including the UN, G20, and an imagined ‚union of low-carbon countries‘ that might be bringing things forward). As I heard many similar conferences on this, I am heading on to a workshop instead.

I then sneak into the “energy street fighters” workshop. There, some controversial discussions are taking place between participants, on how to best foster the creativity of lay-people: One French artist explains that he’s offering some pre-fabricated, lego-like design modules to foster some level of creativity among their users-explorers, especially among uninspired, shy adults. Another participant disagrees, and prefers to foster an open ‚paper & pen‘ creativity, not limited/constrained by lego-like constraints.

The next speaker in that workshop, a social scientist, then speaks about an „information/virtual revolution“ ongoing, with a mediatisation of everything, a transformation of space & time, a democratization of knowledge (and many more big words used excessively by the speaker)… but also with ‚grave dangers‘, because powerful mechanisms of control can arise from it. Between swarm intelligence and facebook, he warns that the “participative” technologies experimented with by media artists, may end up nourishing a „Technofinanzmachine“, and asks for a high degree of critical caution to accompany experimental practices.

I also visit, twice, the ongoing performance of Ian Civic during this afternoon. The performer stays, during the whole festival, in a white-room (with walls and ceiling covered with bright white neon lights), on a big white stage in the center. At my first visit, he’s sitting on a chair, wearing high-heels, staring in front of him with an empty look. At my second visit, he’s sleeping on a white mattress integrated in the stage, with a silver sheet covering him. The room is a-septic, and the performer is feeling absent, looking very tired already (after 18 hours of continuous performance). The audience looks, silently, but no communication whatsoever is emerging. The atmosphere is rather sterile. I will visit him again later, on the Saturday…

At 19:30 is the world Premiere of Kris Verdonck’s performance Exit. The aim of this performance is explicitly to put the audience to sleep: In his conference intervention earlier on the same day, Verdonck explained why: Sleeping allows us to take much better, deeper-reflected decisions, according to a neurologist (who, in a video projected at the beginning of the performance, gives a short lecture about this topic). More especially, dreaming allows the mind to order its memories, to discover rules, and to make meaning, at a more-than-conscious level (which relates also to what I call the “autoecopoietic” processes of the subconscious, in my book Art and Sustainability). The performance is therefore conceived as “an hour of dreaming away”… What is to be seen is a short choreography of contemporary dance (a solo), which repeats itself over and over again, with a very soft minimal music, and the lights gradually shifting their colors and dimming down very slowly. Only in the last 5 minutes does the choreography change, first in total darkness, and then with lights coming back – a proper “wake up call”…

Rather than falling literally asleep, I do let myself feel half-sleepy, half-watching the repeating movement patterns, and dreaming away for variable periods of time. But this is actually not so different from many contemporary dance performances I watched in the past decades, where I was also induced into moments of free-running day-dreaming

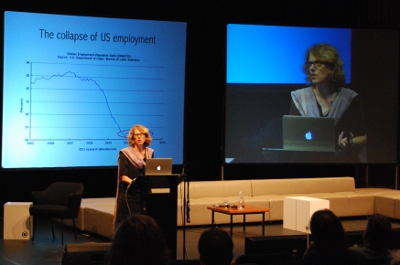

Finally, I follow the conference by Juliet Schor on “post-fossil consumption”. Schor advocates for the reduction of working hours in wealthy countries, accompanied with new, time-intensive, money-unintensive, income-earning opportunities that form part of an alternative economic circuit based on sharing – a sharing economy as in for example car sharing, couch surfing, tool libraries… Schor also discusses pathways for people to become producers in a different way, achieving high-tech self-provisioning: urban gardening/permaculture, alternative home constructions, micro-generation of energy, „fab lab“ small scale manufacturing… replacing things people would have purchased, but also requiring higher ecological knowledge.

Over the night that followed, I believe I dreamt about dreaming… A resurgence from the performance Exit…

Second festival day (August 19th)

I am back to the festival around midday, unfortunately a bit late for Nnimmo Bassey’s conference session. I can only hear his last words, on how he imagines a future, sustainable Berlin: Some things will disappear (such as tropical fruits all year round in supermarkets) but people will be more connected with nature & with one another.

The next session in the big auditorium is a live stream (via satellite) from Nairobi. It’s managed from there by the artist Sam Hopkins. He’s introducing and interviewing several local NGOs, organizations, or projects founders. Among them are:

- „Chocolate City Tours“ in Kiberia – that stands in contrast to the usual ’safaris‘ in Kenya, which avoid the urban spaces and slum neighborhoods ; the guest speaker talks about the talent potentials in these neighborhoods.

- „Green Thumbs“ – a platform for youth empowerment, freedom of expression, fostering curiosity & movements, and addressing diverse issues such as e.g. the „flying toilets“ (i.e. the nickname for the used toilet paper flying around in some slums where public toilets are rare); they also provide small commercial services in the slums, which help finance their other projects.

- „Formada“ (forum for resource management & development advocacy) – based in Dandora, Africa’s biggest dump site according to Hopkins. The site is both a big polluter and a big employer. Formada’s speaker, Jackson Mussuma, explains that the initiative started as a school project, in 2004. After finishing highschool in 2006 the teenager-organizers continued the project as a NGO. They do environmental education at schools, and alert the people about the negative effects of the dump site (which is difficult because, although it negatively affects 300 000 people, the site also employs 6000 people). This NGO is self-funded, by its members , and lacking external funding.

- „JCC (jobless corner camp) – talk active“ – catering to the “emotional sustainability” of the unemployed, with meetings in the streets where people are “not just talkative, but talkactive”. However, this organization is having some difficulties too, as the State and the police don’t like seeing people meet on the streets, because of the fear of social unrest.

- „SPI – it’s your responsibilty“ – the Swahili name of the organization means “standing together”: The guest speaker, named Beatrice, lists their activities, dealing with environmental and with violence issues. They have a peace project, with street shows & drama, but also workshops & training. In another project, they are picking up and getting rid of plastic bags.

- „Loos for life“ – building community toilets in one slum of Nairobi, deals with the failing provision of public facilities. The guest speaker talks about her inspiration from James Baldwin,whose texts she reads to the children.

- „Al Hazira“ – a small pirate radio (radio licenses are expensive in Kenya), with the slogan: „reliable rumors“…

Overall, Hopkins‘ session shows that Nairobi has a vibrant ecosystem of local social-ecological organizations, many of which are managing to exist, at a small scale, with no or little external funding.

Later in the auditorium is projected a video (sent by the parallel festival in Delhi) by the artist Chris M. Green, about the megacity of (New) Delhi. The video touches several topics, including the fact that about 90% of the city is unplanned, and the colonial history of the city. The video shows the location for the official founding of „New Delhi“ by George V, a monumental site now in the outskirts of the megacity. Green also criticizes the contemporary planners‘ opposition against the pre-urban, rural-urban elements in Delhi, and against marginals. Both are threatened by the planners in some locations. The video discusses one example of such an urban development plan, criticizing the threat of displacements, and the fact that, for example, there will be no more grazing allowed for goat herds…

In the afternoon, I’m visiting the discussion session with the Laboratory of Insurrectionary Imagination (LABofII).This group designs experimental methods and passes them on to civil society activists. Among these methods is the famous “Rebel Clowns Army” that gained a huge fame in its artivist actions alongside major protest actions (e.g. during some G20 meetings).

They explain that their big ambition is to change the way politics is done, and to create a radical political space that is as sexy as capitalism. Only facts & figures are not enough – there’s a need for the imaginative, for intuitive desire, to get into politics, especially on social-ecological themes. But their work is also about creating niches of postcapitalism – to live postcapitalism in the present.

LABofII’s work is inspired by Courbet’s involvement in the Paris Commune (considering it as the peak of his artistic development, unlike art historians). They also take inspiration from the model of permaculture: learning from ecosystem resilience, for designing human habitats.

About the clowns army, LABofII explains that clowns naturally transform the world through disobedience, and that using archetypes in politics is powerful: Archetypes bring about things that are easily understood. Besides, clowns are in-between, liminal characters, funny & scary. The Rebel Clowns Army works with confusion rather than confrontation, unlike the ‚black blocks‘.

The LABofII then also describes how they got first invited by the Tate Modern for an event, and then the Tate tried to censor them upon realizing that their work is about genuine activism and not only “talking about” activism. The whole thing ended up (after the oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico, that happened just in between) in a number of actions denouncing Tate Modern’s submissiveness to its sponsor BP.

A similar issue happened when the curator of the exhibition RETHINK in Copenhagen in December 2009 (alongside the UN Climate Conference “COP15”), canceled LABofII’s participation, which consisted of redesigned bikes for climate protesters in the streets. Luckily, an activist organization was braver than the art institution, and took on itself to invite LABofII ; some of the bikes were used in the streets (although many were confiscated beforehand by the Danish police).

In the run-up to the ULK (Ueber Lebenskunst) Festival, LABofII organized a 10-days workshop with local participants. Its title was “think like a forest”. The aim was to show how art activism & permaculture are symbiotic, and together giving an inspiring & fruitful framework. They explain shortly how a typical LABofII workshop aims to create “radical friendships”, creating deeper trust in the group, reaching consensus. This is also inspired by Beuys‘ idea of warmth – creating warm spaces. The end ‚product‘ of the “think like a forest” workshop can be seen on the website www.blacklocust.me – it deals with a specific plant species which can grow through concrete, and with seeding that plant near the headquarters of ‚climate criminal‘ companies…

I ask the LABofII team (Isabelle Fremeaux and John Jordan) to also tell us about their upcoming permaculture project in Brittany. They have a feeling of frustration with the excessively temporary nature of their experiments. They want to find a space where one can work on a more permanent basis, and to found a permaculture school. They are now in the process, together with other partner-organizations, of buying some land and establishing “la r.O.n.c.e (Résister, Organiser, Nourrir, Créer, Exister)” a center for such activities, somewhere in Brittany (France).

On the evening, I am visiting the conference again, for the session on “sustainable action”, and am rather disappointed by Harald Welzer’s arrogant and simplistic arguments. He does make a number of good points, about the need for alternative practices and experiments (Gegen-praktiken und Laboren), rather than mere abstract knowledge. Welzer argues that what matters is what can influence „lebenspraktische Situationen“ (life-practical situations), not complicated discussions about climate change urgency or discourses on over-population. He pleads for a re-politization of discourses, instead of technocratic talk, high-abstract ‚complexity‘, and ‚world society‘ talk.

But overall, his discourse is only superficially provocative, and totally mixes up “complexity” and “complication” (as a Brazilian speaker later points out, live from Sao Paulo, at the very end of the session). In short: For Welzer, the ecological crisis is something very simple to understand, that a 9-year-old grasps immediately, and all the talk about complexity is just mystification.

However, what Welzer is totally missing here, I would argue, is that the abstract, rational discourses he’s criticizing are often not genuinely complex. What is really complex is everyday life, and nature: Complexity is the spider that weaves its web during a thunderstorm (as David Abram wrote in The spell of the sensuous). And complex are the complementary tensions forming resilient ecosystems… The genuine sensibility to ecosystemic complexity that we need to foster much more (as I’m arguing in my book Art and Sustainability), is being ignored here by Welzer, or confused with the artificial complications of intellectual discourses.

Third and fourth festival days (August 20th and 21st)

On the Saturday, I’m catching the end of Tim Jackson’s speech on “prosperity without growth”. He’s arguing that a new economy requires a shift of investments, towards genuinely ecological investments, i.e. in ecological & social assets, and not profit-driven. It also requires ecological enterprises which are service-based, providing capabilities, and supporting communities, and which can better cater to social & psychological flourishing than consumption society. For Jackson, productivity growth doesn’t make so much sense in those services that contribute to quality of life. Prosperity in his sense is about the ability to flourish as human beings, rather than about productivity growth. He also stresses that the human self is not only selfish and seeking novelty, but also altruistic and seeking tradition. However, the current economic model only caters to the first two.

Later on, I am joining a workshop led by Arjun Appadurai. The workshop is the occasion to learn about one NGO that Appadurai has been running for now 10 years in Mumbai: „PUKAR: Partners for urbam knowledge, action and research“. Appadurai starts with a short autobiographical exercise, explaining that he eventually ran into Indian urban housing activists, and that this encounter met his own interest in the relationship between research & activism… How can academics have a fruitful dialogue with people doing social change? This not an easy relationship, Appadurai points out. He introduces the city of Mumbai to the workshop participants, stressing that the city has very few critical, academic institutions, and very few spaces available for gatherings of progressive artists and intellectuals. PUKAR is doing research & training of researchers, most especially with the „Youth fellowship program“ (funded by Tata): Young adults in their 20’s (80% are from lower and lower-middle-class) are selected on the basis of their projects or a specific issue they need to address in their lives. The training takes place on weekends, evenings, holidays, and includes both basic techniques (e.g. photography, statistics), and skills in writing and presenting-communicating. There are now 1500 alumni, „barefoot researchers“. The program has produced an immense amount of data, which is however put to little use yet (apart from a couple of partnerships with foreign research institutions). This raises some questions among the workshop participants. But, Appadurai argues, what matters is not so much the knowledge gained. What matters is the “enabling experience”, bringing to these barefoot researchers the “capacity to speak up in your city”.

I’m feeling slightly uneasy with one aspect: the rather traditionally disciplinary list of social science methods mentioned by Appadurai, and ask him about the risk of maybe ignoring other methods, coming from the students themselves, and other (non-Western) forms of knowing reality. Appadurai connects my question to Polanyi’s idea of “tacit knwoledge”, but defensively argues that “we should not deny our research methods to them” – he doesn’t really seem to come to the idea of a transdisciplinary approach, and he definitely doesn’t want “Deleuze, Derrida, Debord-situationism or advanced contemporary art” to be associated to the program. It has to stay basic, down-to-earth, easily accessible to the students. Appadurai further connects this initiative to another slogan he’s advocating for: „The right to research“. Research can be a human right. Local knowledge & empowerment are good, as international NGOs are already stressing, but local knowledge is in itself no longer sufficient when it comes to global warming for example. We need capacities to know these new things. Until this capacity is radically democratized – people capable of adding to their own knowledge themselves, empowerment won’t be enough. (I totally adhere to that line of thought articulated by Appadurai, but would wish a less traditionally disciplinary social-scientific perspective to be proposed as part of this research-capability building.)

I have to leave Appadurai’s workshop half-way through, in order to attend a live performance streamed from Delhi, in the main auditorium. The performer is called Inder Salim. His „Earth – Territory – Music“ performance is anything but convincing – an instance of “roll-yourself-in-the-dirt” performance art as another festival visitor calls it during a conversation later on.

More generally, I am disappointed with the performances program of the festival, as far as I could experience it, with a few exceptions (but I unfortunately missed “Walden” – the long night of performance on Friday). However, I must salute the courage of experimenting with live-video streams instead of inviting the foreign performers to fly to Berlin. Alas, the result, as it appeared in the HKW auditorium, is of very low quality: Bad video, an awful sound, and many cuts in the satellite stream… Not to mention that much of the ‚feel‘ of a performance does not convey across the screen so well, especially not with such bad technical conditions.

Later on Saturday, a live performance from Sao Paulo is presented by the group “Teatro de Narradores” – a filmed street performance, interacting with passers-by, listening to their hearts and pointing a gun at them – not bad, a bit more moving than Salim’s performance, but not very convincing either. I am also visiting again, on the last 2 days, Civic’s long-duration performance “Welcome Home” (which I already mentioned above): I now see Civic showering, Civic dressing up some extravagant clothing, very slowly of course, and Civic quoting Thoreau’s Walden in sign language, always with this empty look in his eyes… purged and sterilized by a long tradition of white-box modern and postmodern art.

On Saturday evening, a bikes-disco is on the terrace. To get the music running, people have to invest some sweat, pushing on the pedals. It’s a lot of fun indeed and the Djs are nicely fooling around.

On Sunday, the live performance streamed from Saint Petersburg, by Iguan Dance, is also only half-convincing. But its topic and methodology are very interesting: This is a duo of dancers/choreographers who are staging unannounced, unauthorized, contemporary dance performances in supermarkets, about consumer life and personal struggles. It is a pity that the live performance on Sunday is not itself staged in such a supermarket situation, but in a safe art studio instead.

The young adults of the ULK Camp, who have been living on the festival premises for 5 days, are also presenting a performative work on Sunday afternoon. Even though it feels much like a school-show, the idea is nice (an archeological look back at our time, from a perspective 100 years ahead).

I also visit several times the long-duration performance/installation “1/2” by Benjamin Verdonck: the material installation itself is unconvincing (a few sculptures and two stands where half-sausages and small-size drinks and cigarettes are being sold), but it does create a nice social setting, and I’m meeting friendly people there. The piece is near the Foster Dulles street, a bit apart from the other locations, thus a bit relaxed and off-the-track somehow. Among the people I meet there is the artist himself, Benjamin Verdonck, with whom I have a couple of conversations: We have some interesting exchanges about art and ecology, we exchange our books, and I realize that the guy’s work and his personal world, are much more interesting and meaningful than what a quick look at his installation “1/2” made me believe at first. I’ll sure try to keep in touch with him and exchange further.

I also visit, during the festival, a few noteworthy installations on the roof terrace and in the building, by contemporary artists including Das Numen and Learning Site. These are e.g. recycling, composting, energy-saving installations, exemplary for the kind of work done by these art groups, and dealing with the sustainability of the HKW building itself.

Back to the talking heads in the big auditorium: On Sunday, I am attending two very contrasting Asian keynote lectures: Vandana Shiva on “Earth Democracy”, and Chandran Nair on State policies.

Charismatic and invigorating as always, Shiva makes a vibrant plea in favor of a renewed understanding of democracy. We’re experiencing a deep cultural crisis, she explains, characterized by:

- our inability to understand how to live on this Earth -, and

- our inability to think in terms of diversity (cf. Samuel Huntington’s “clash of civilizations” as a symptom of this autism) – we’ve built an alienated idea of who we are. This makes it impossible for us to be fully human, and to design a future for our species.

Taking us out of this crisis, an “Earth Democracy”, in Shiva’s eyes, would be characterized by:

- living economies, not killing economies

- a living democracy as the practice of freedom in everyday life, for the poor, and „for the last species“ (freedom for all species to evolve) – „our freedom has to be premised on the freedom of all species, and of all humans“

- reclaiming our identities as Earth citizens

- no more a culture of death in the mind, but living cultures

- the defense of the commons, with e.g. resistance against grabbing of land by speculators, and also e.g. intercultural gardens, as in Berlin, as celebration of peace and diversity.

Chandran Nair is, as the last conference speaker on Sunday evening, taking his audience down a much darker road. He advocates for “strong governments”, and more especially authoritarian Asian regimes, as the only ones who may be able to impose ecologically sound restrictions and limitations on consumption by their peoples. Nair does not value democracy, nor individual freedom, very highly, and prefers to impose strong rules in order to guarantee “basic rights” to everyone. In his mind, the Western democracy model has failed to show the way towards sustainability. European governments change directions at every election, he argues, and their ‚greening‘ policies are just ‚public relations‘. CSR is an oxymoron. Companies don’t do less, they do more. To think that they can bring sustainability is a gross lie. But what they can do is obey rules… Companies can be more efficient, but not voluntarily. Individual average citizens are no better, in Nair’s eyes, and thus restrictions have to come from above. “Rejecting consumerism will require very strong governance in Asia […] Freedom of speech will have to be subservient to the vitality of the ecosystem. Collective welfare will have to take precedence over individual rights.”

But, as Bernd Scherer points out after Nair’s speech, we have no guaranteed that such “strong governments” would take “right decisions” (to say the least). I also ask Nair about the threats to cultural diversity, but he does not see any problem there – “because we’re not speaking of fascism here, neither of governments that want to oppress minorities”. (However, when I see how, in China, India, Indonesia and elsewhere, cultural minorities are oppressed, especially when they are nomads or aboriginals, I cannot take his words serious.) I finally quit the HKW, and the whole festival, rather stunned by that disturbing, scary ultimate speaker…

Unfortunately, I missed a few promising workshops and interesting discussions at the festival, including the “lazy climbers” workshop (slow tree climbing) and the presentation of school-projects realized as part of the ULK-Schule. I also didn’t get the time to visit a whole range of initiatives across the city, including very successful urban gardening projects.

What I also missed, but in this case, because it was not in the program, was a reminder of other cultural-ecological initiatives that have existed in the past, and a real presence of experienced ecological artists, whether from Germany of from abroad. But the whole ULK program and the festival focused on current, often Berlin-based initiatives, which makes sense.

Overall I experienced it as a nice and welcome event, but with a sort of discrepancy between the conference program (i.e. the big international talking heads, sharing insights one can also find at traditional sustainability conferences) and the cultural program. I would have preferred a conference program that would have had a better fit with the festival’s questions of the “art of living” and of cultures of sustainability, including but also beyond the few provocative insights of e.g. a Harald Welzer. For example, the “cultural crisis” evoked shortly by Vandana Shiva, should have been the starting point for a lengthier, and more specific scrutiny of the cultural dimensions of (un)sustainability.

Fotos: Sacha Kagan